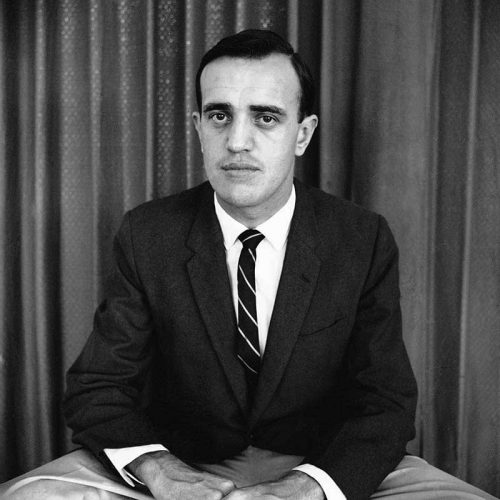

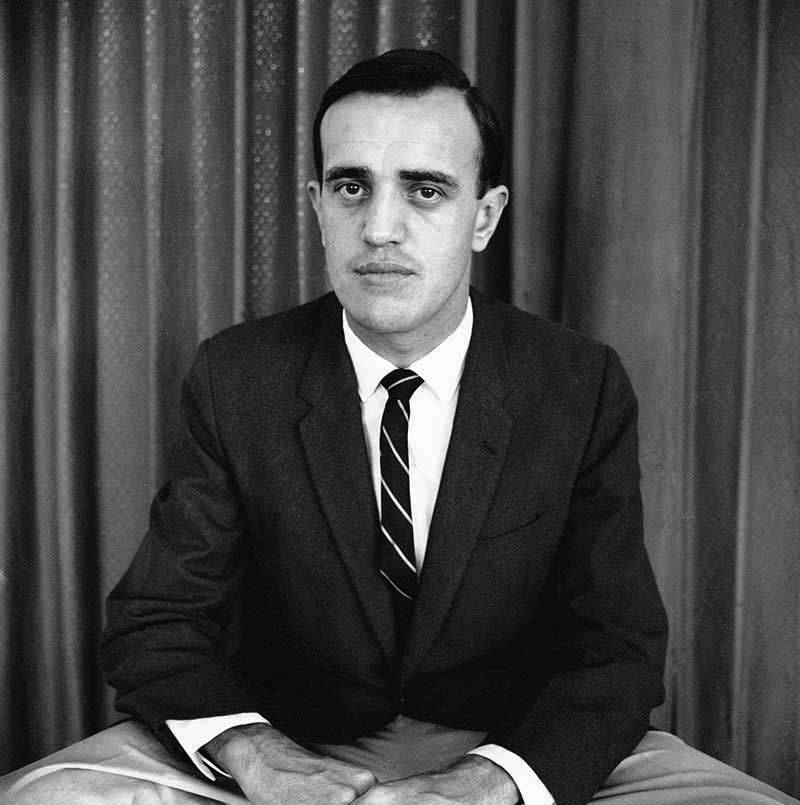

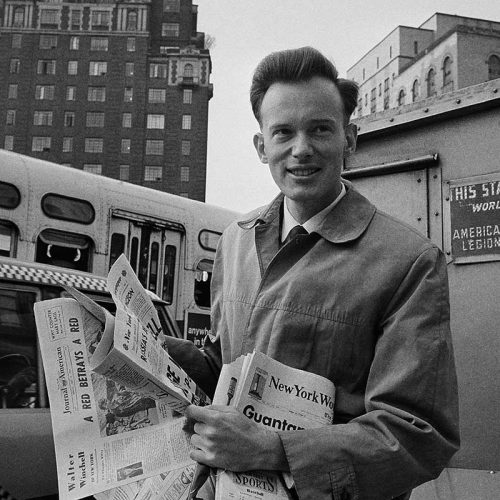

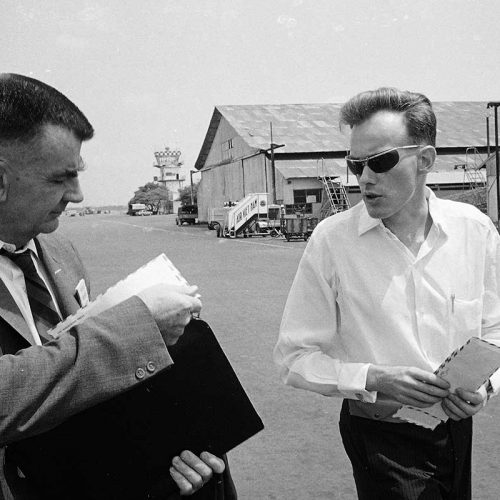

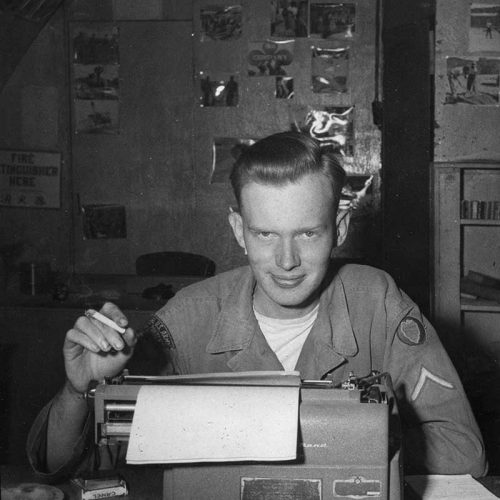

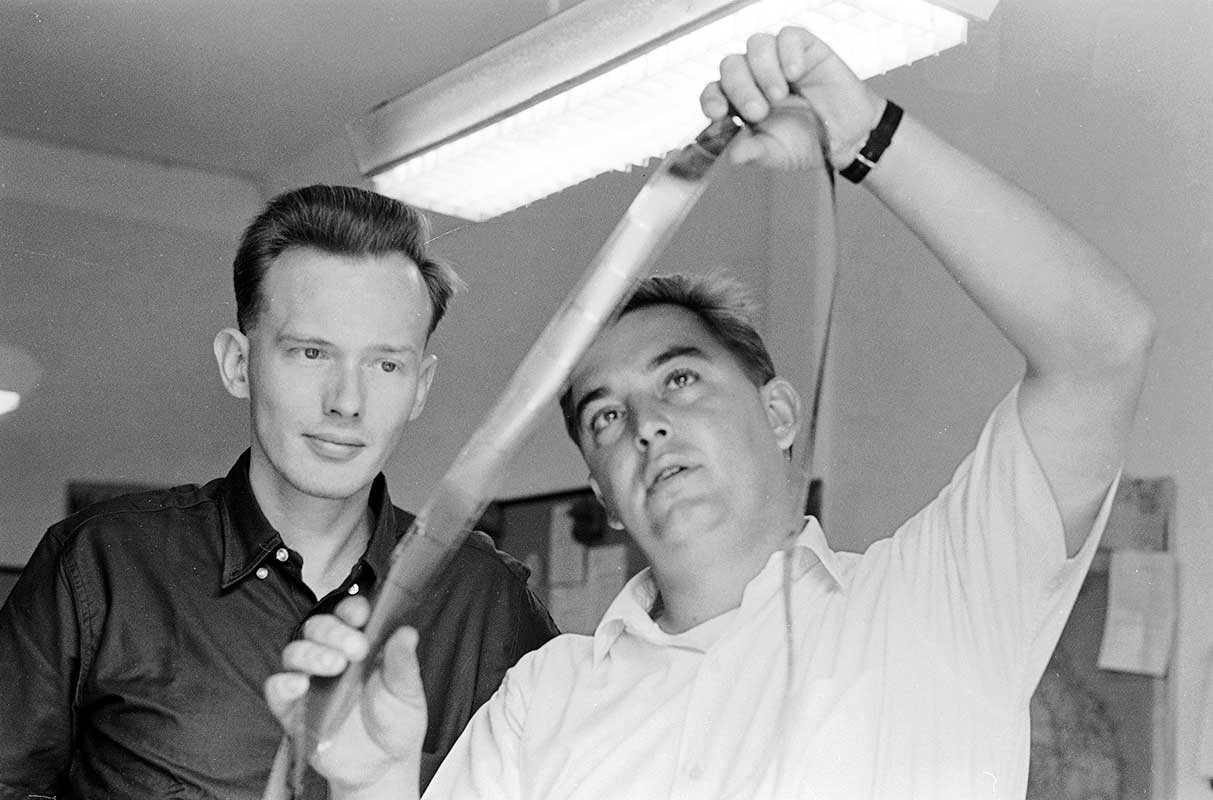

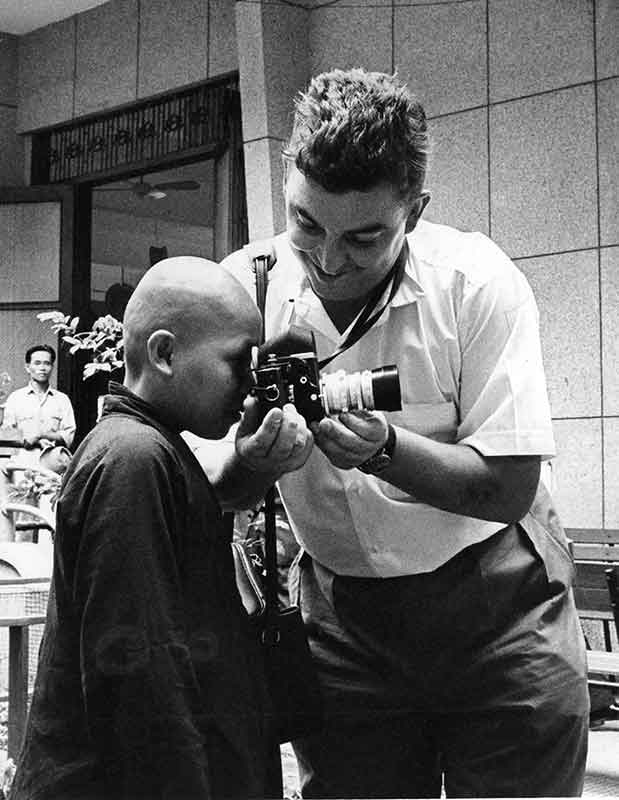

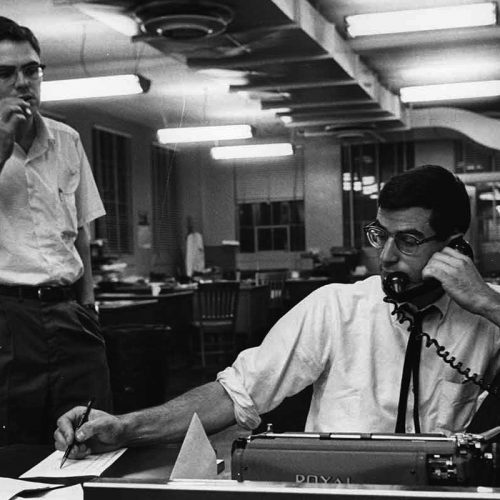

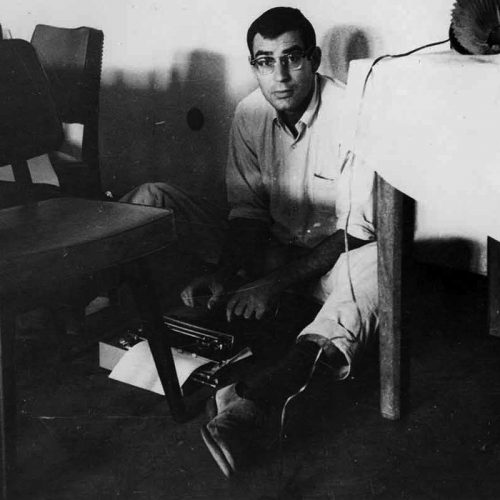

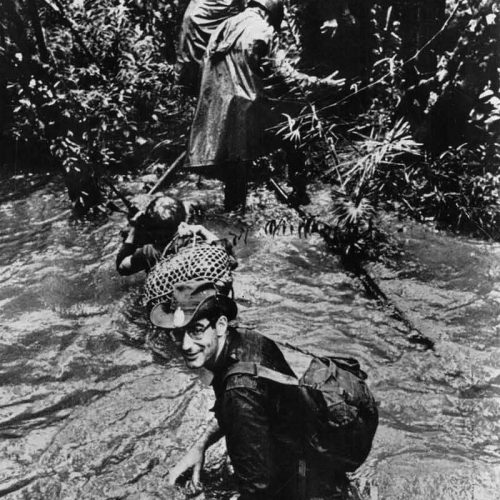

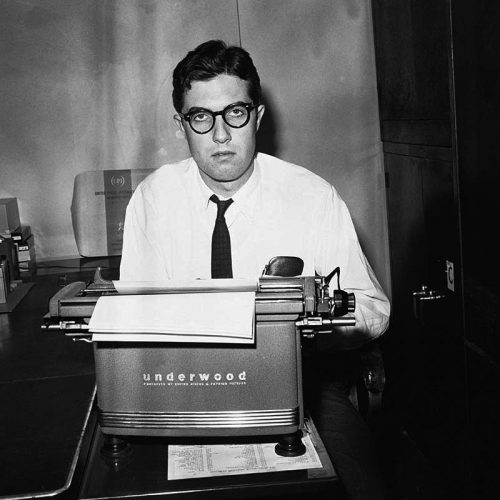

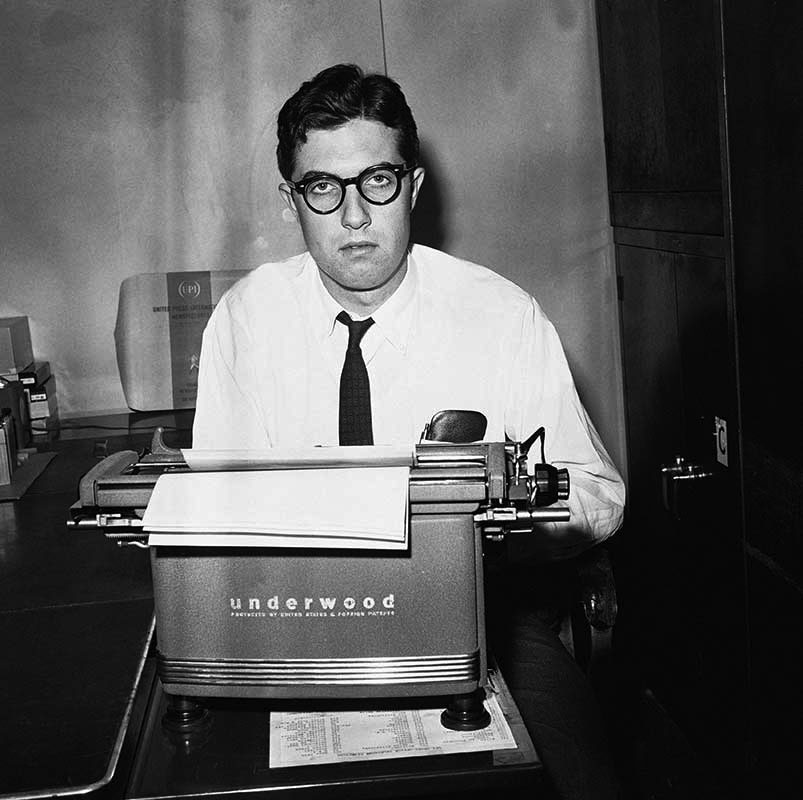

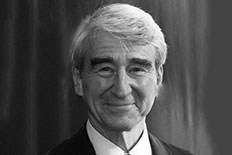

Peter Arnett

Associated Press

Born: November 13, 1934, Riverton, New Zealand

Lives: Los Angeles, CA

Awards: 1966 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his work in Vietnam

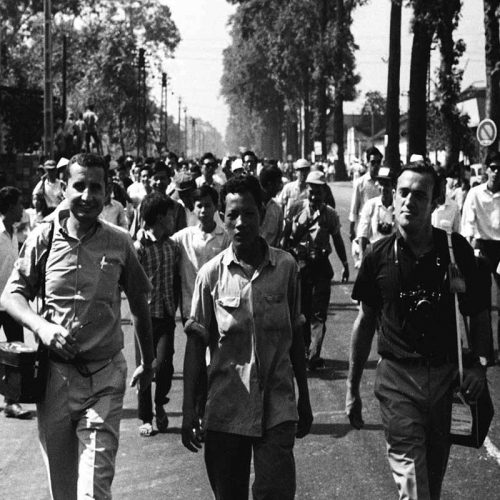

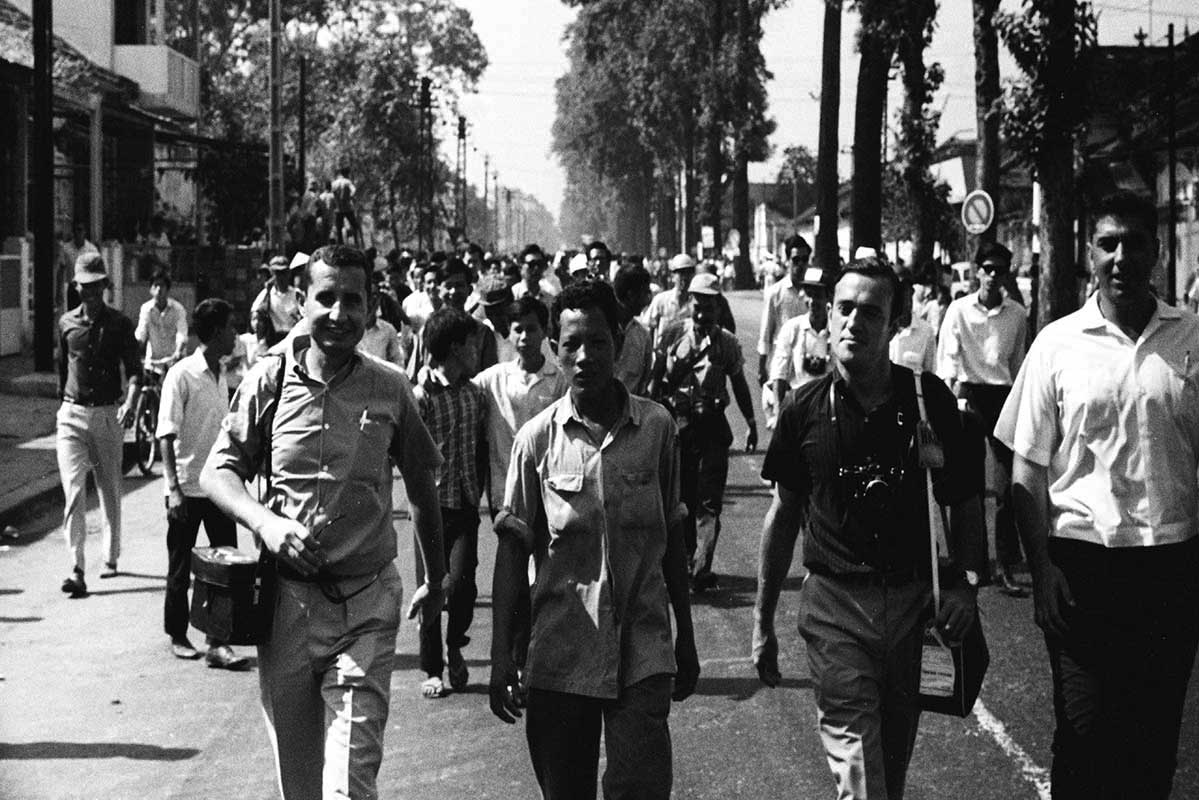

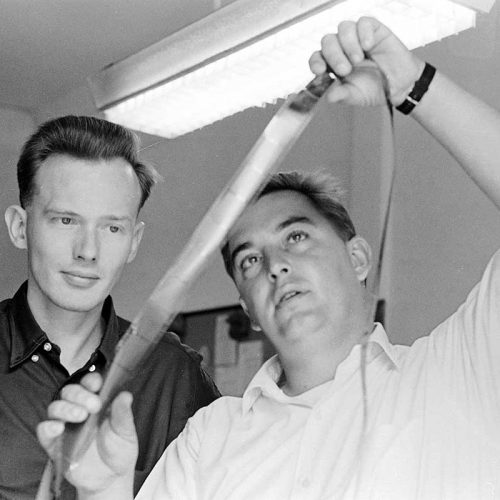

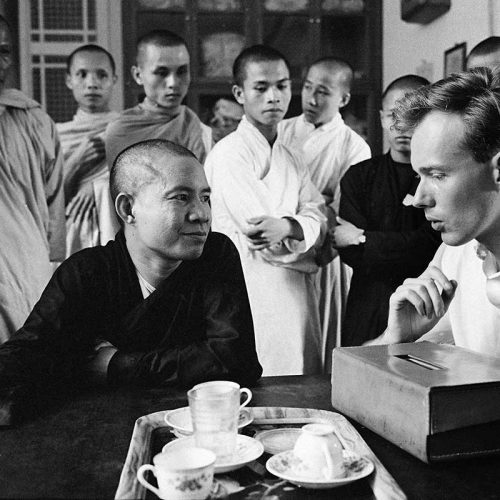

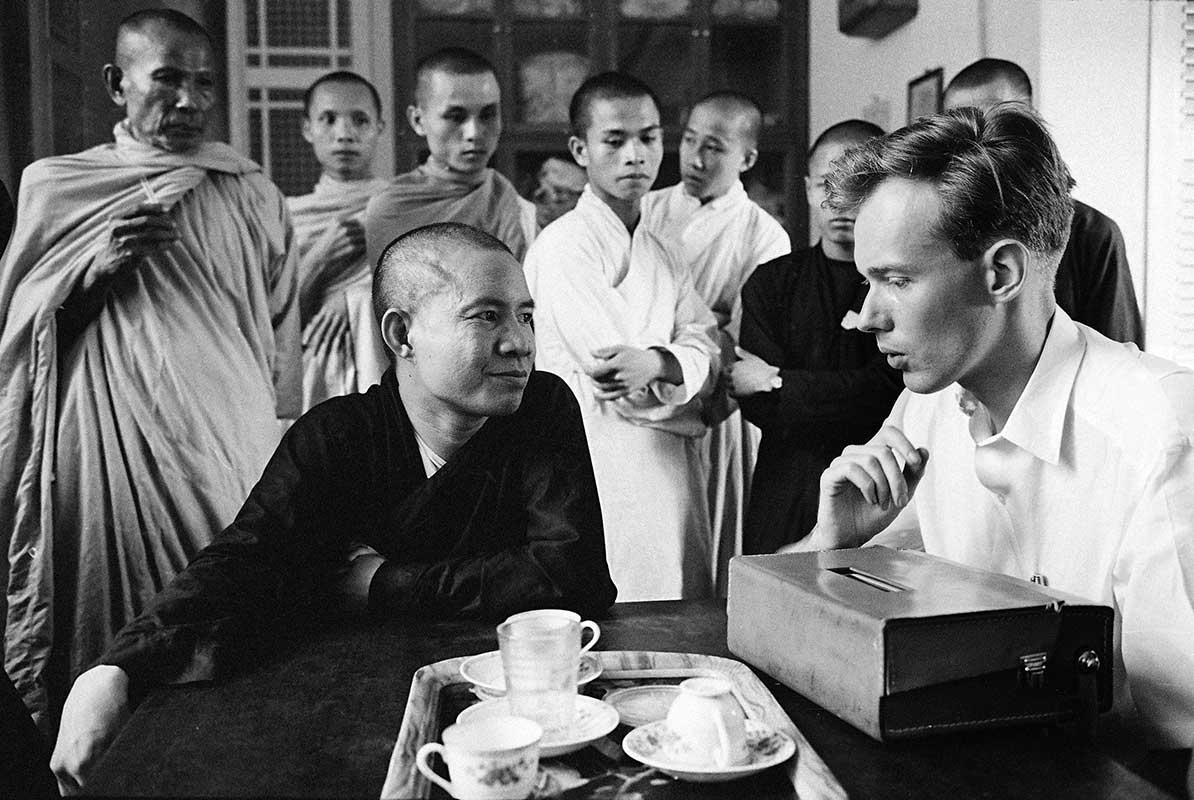

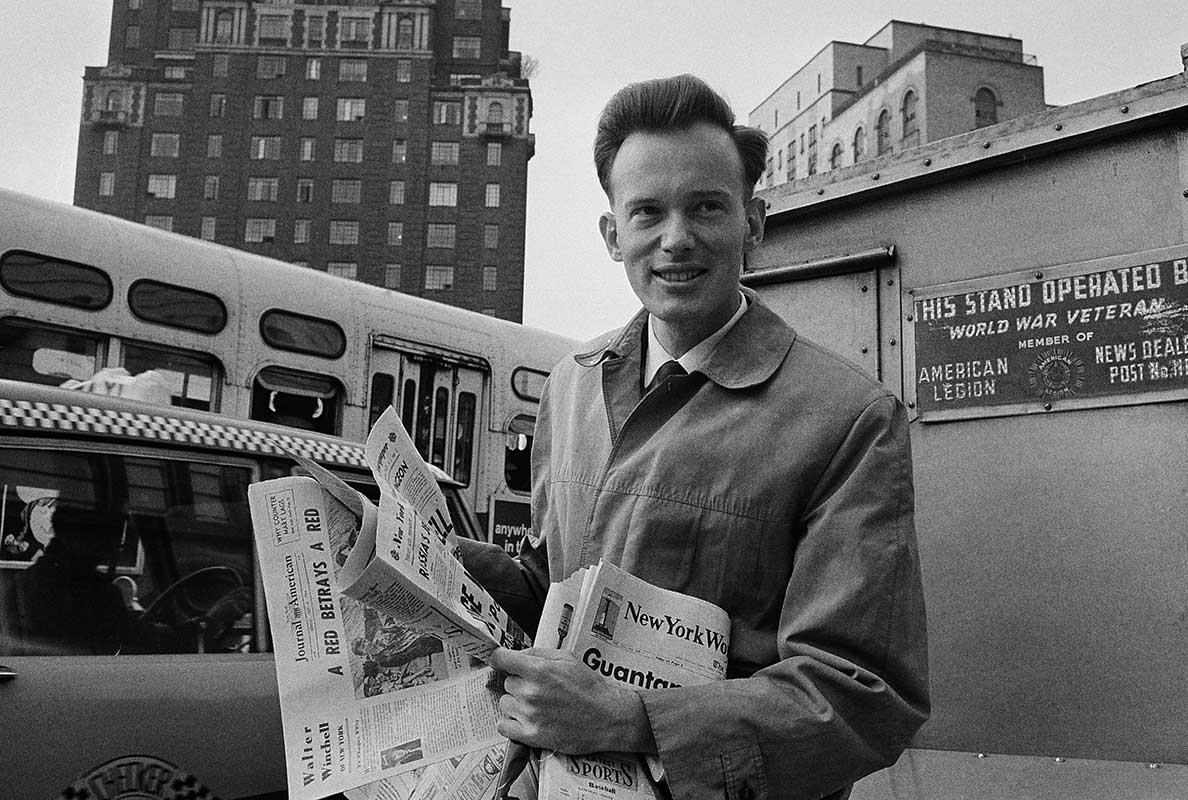

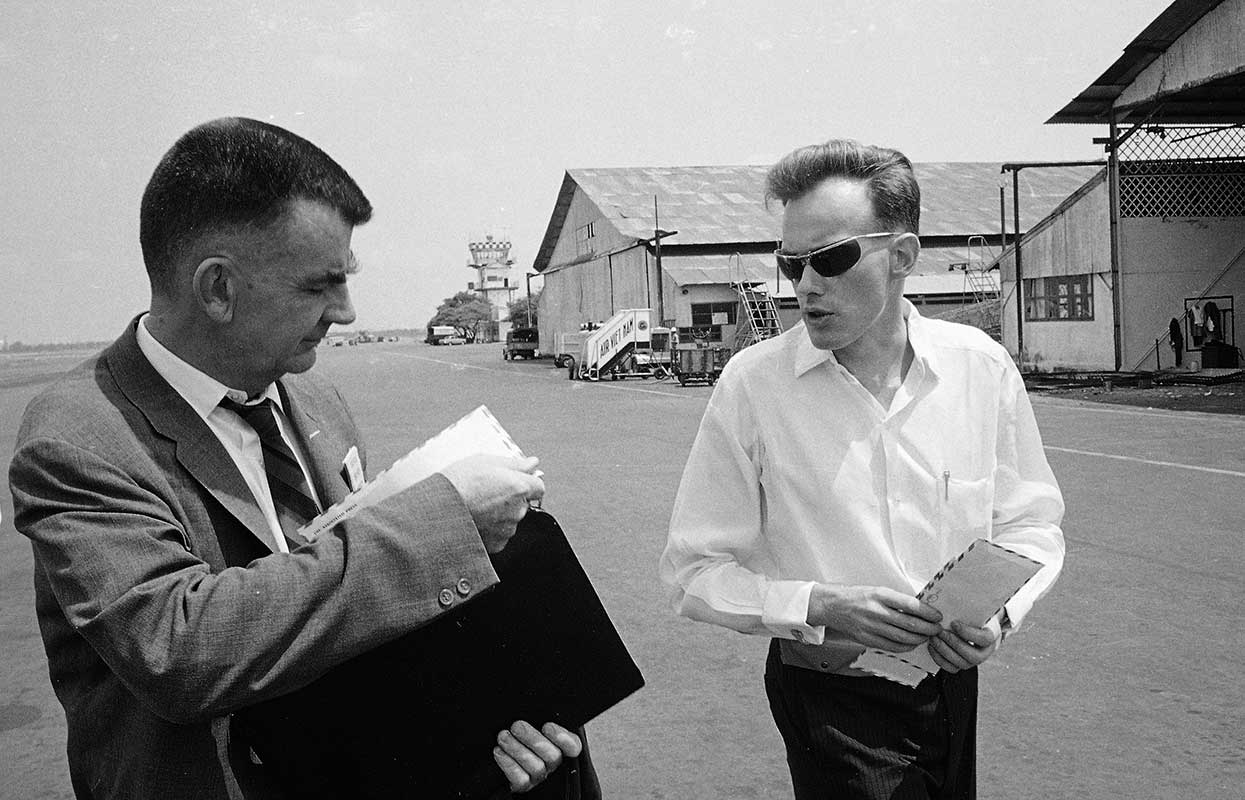

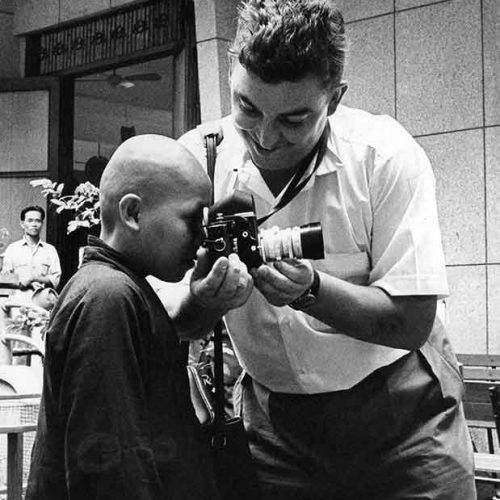

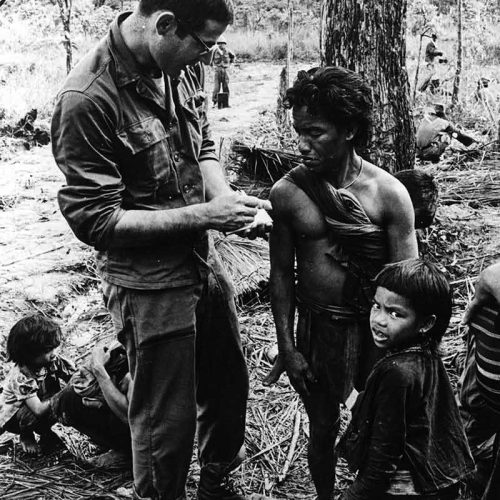

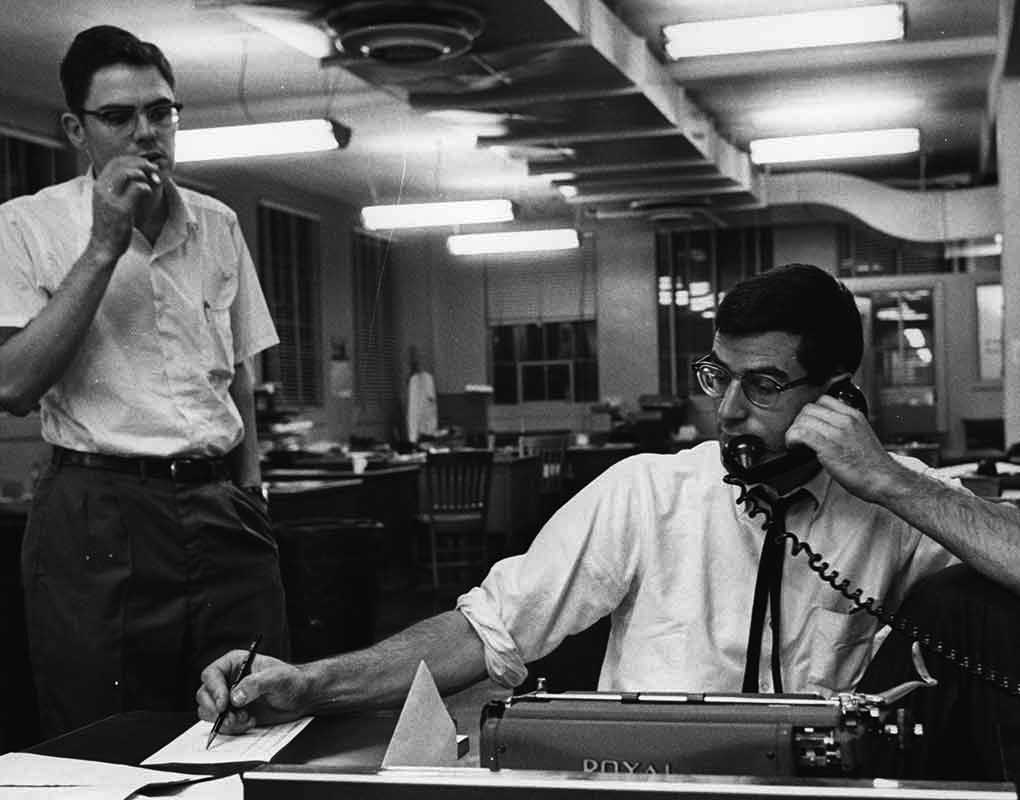

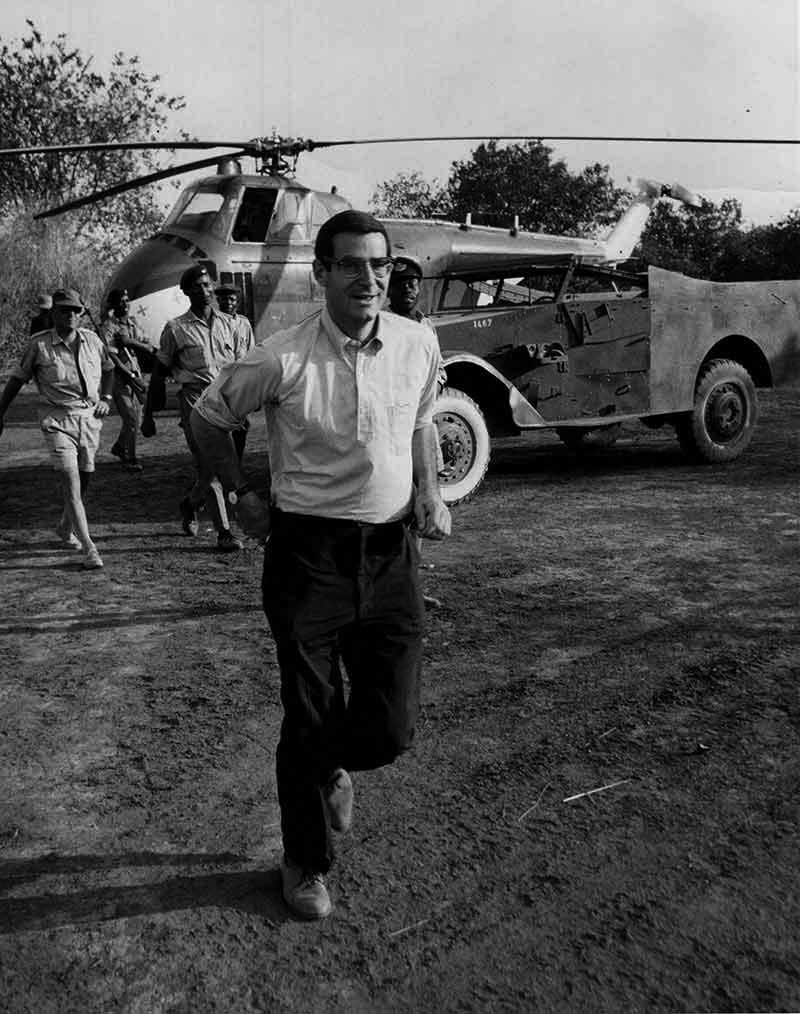

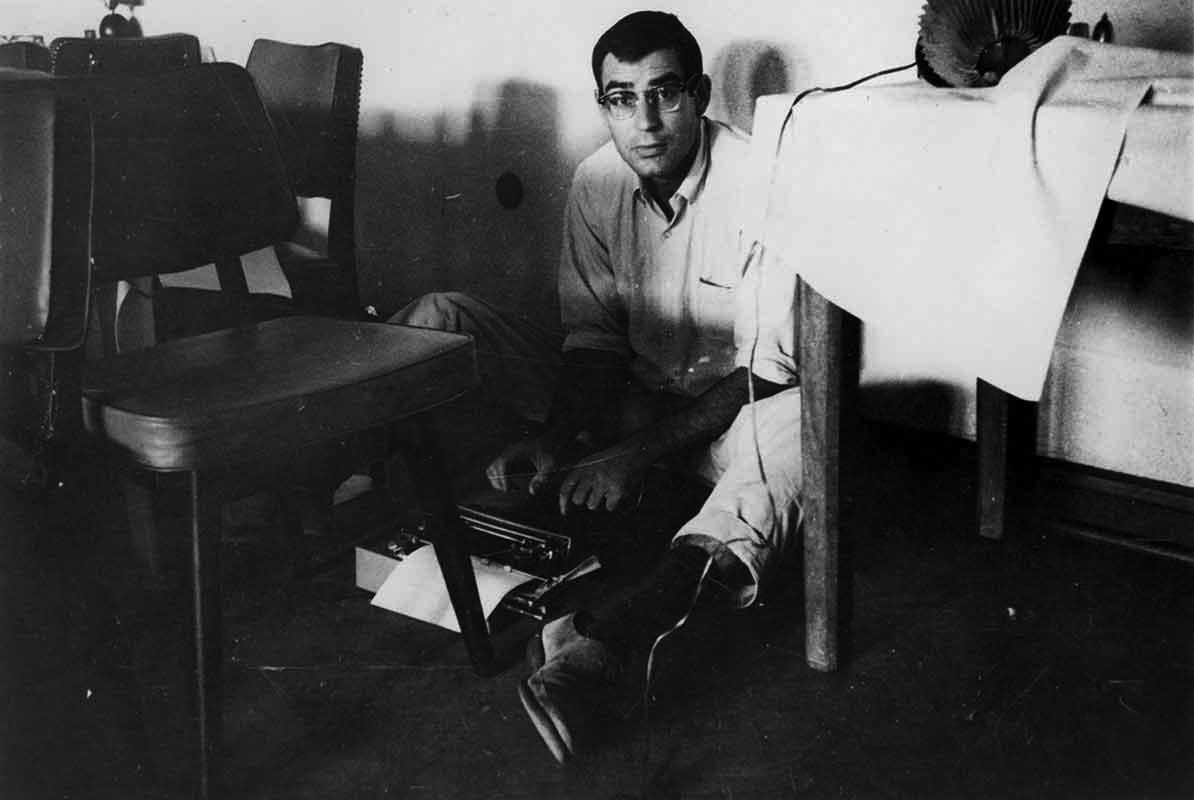

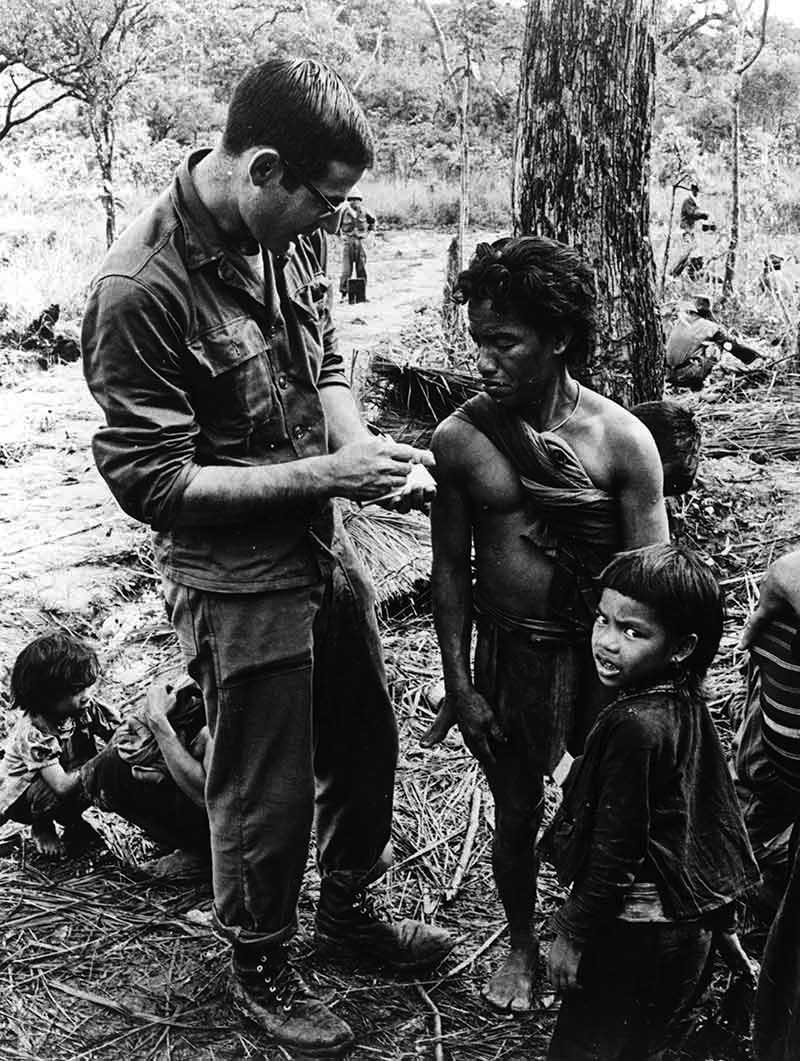

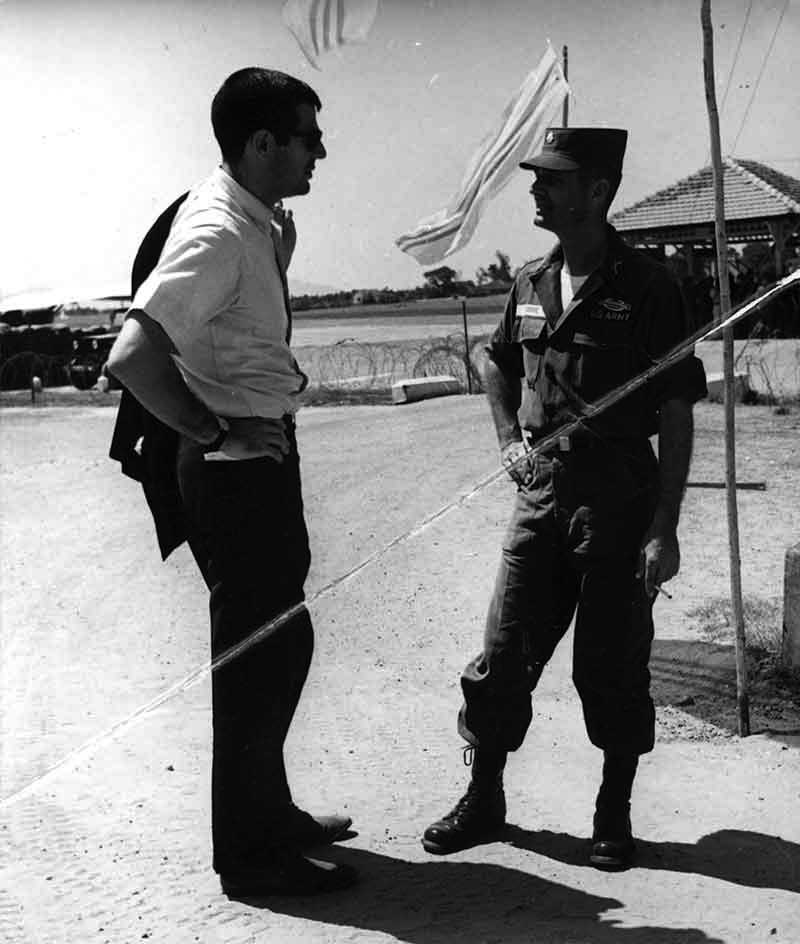

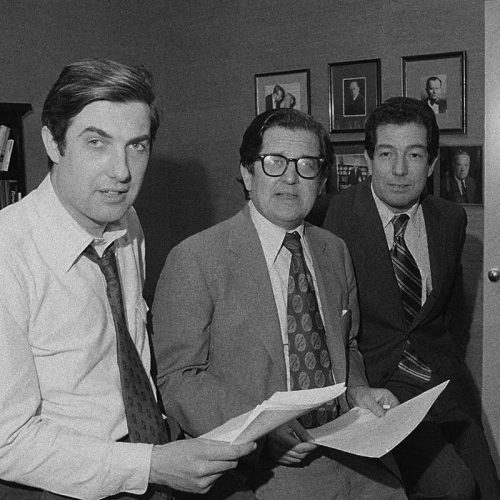

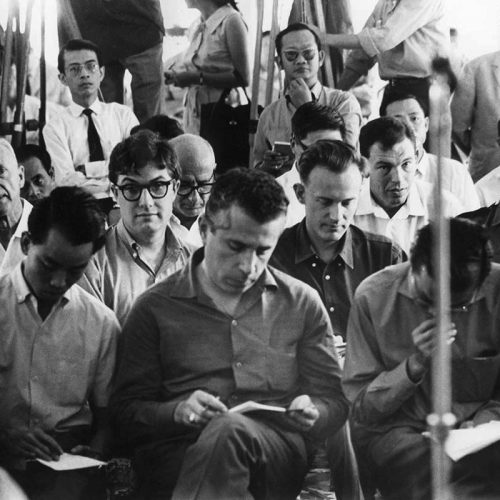

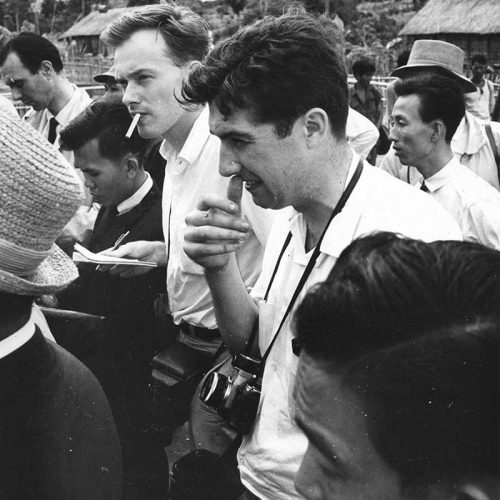

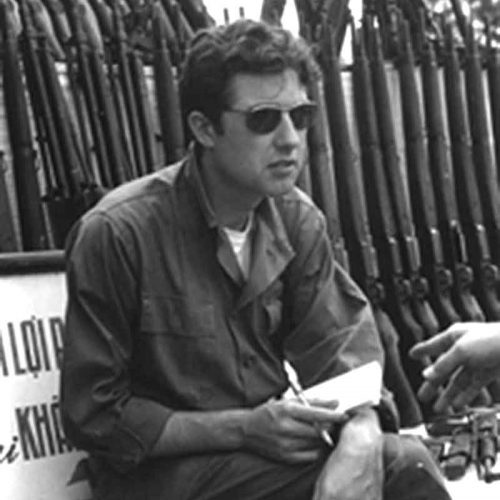

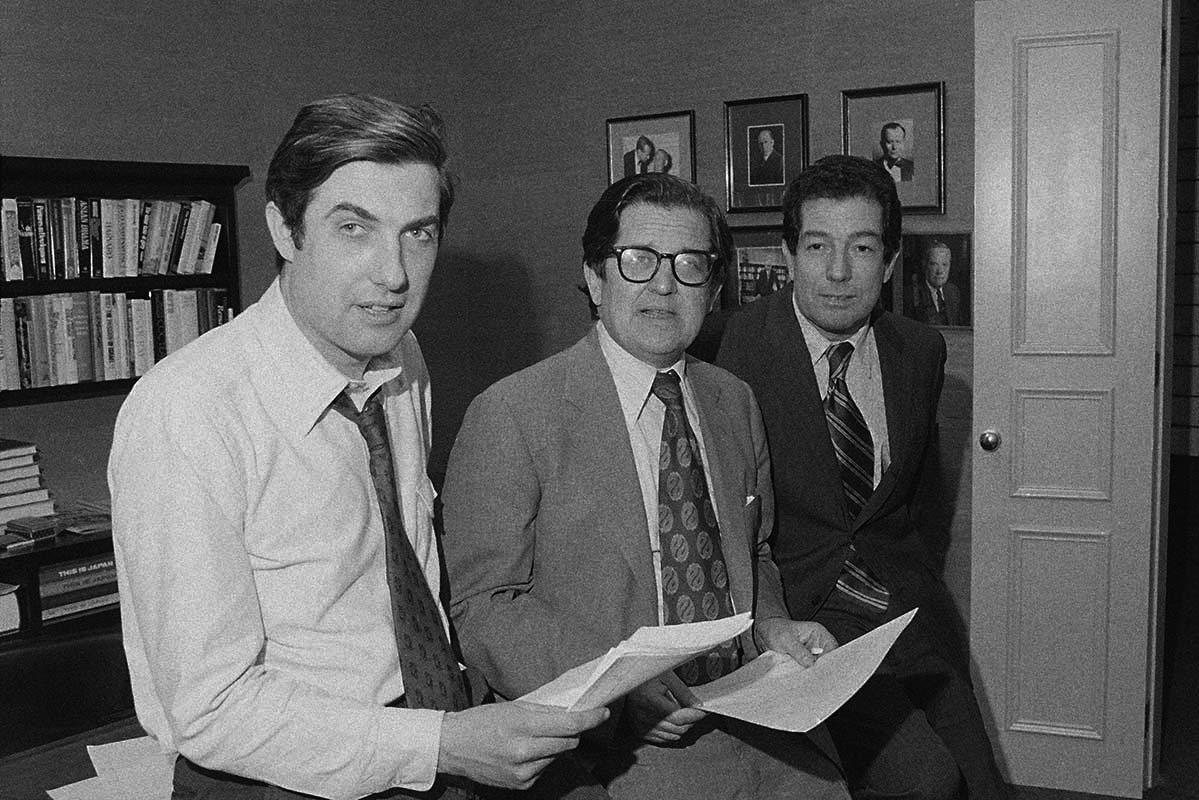

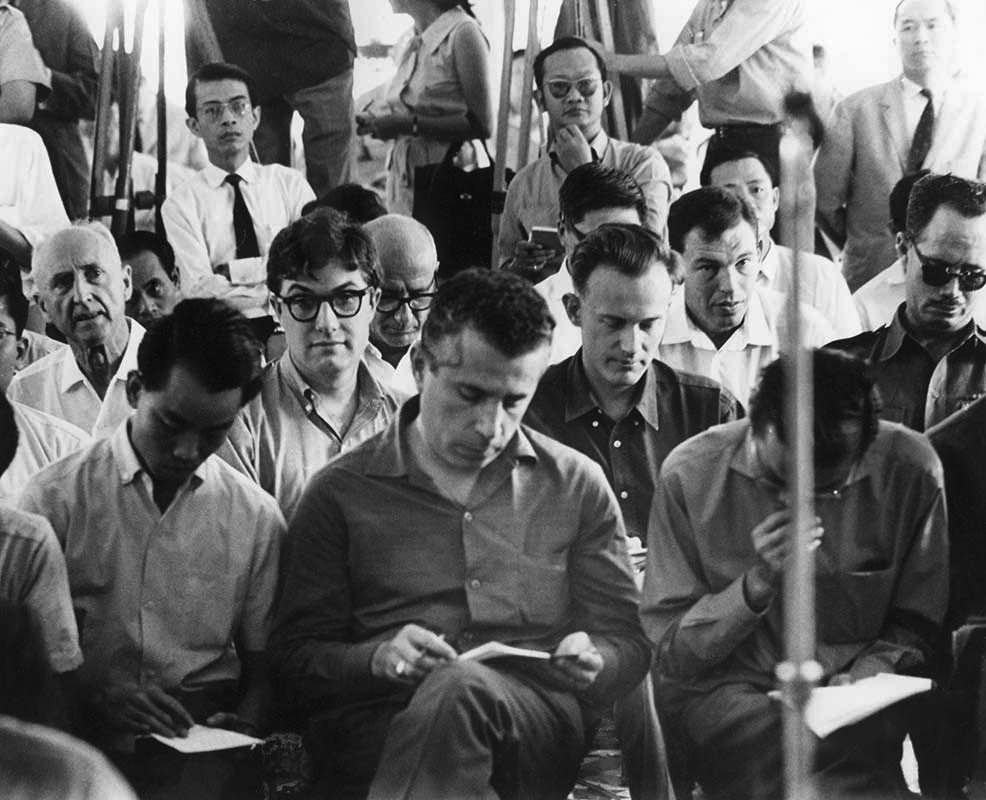

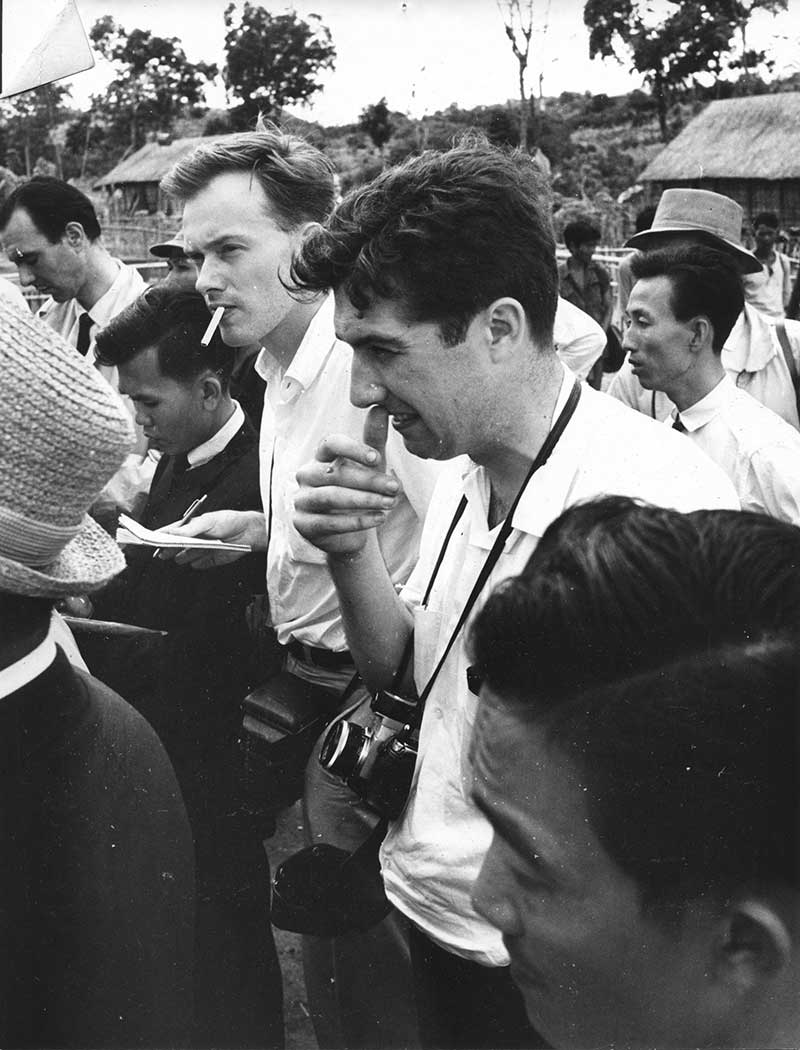

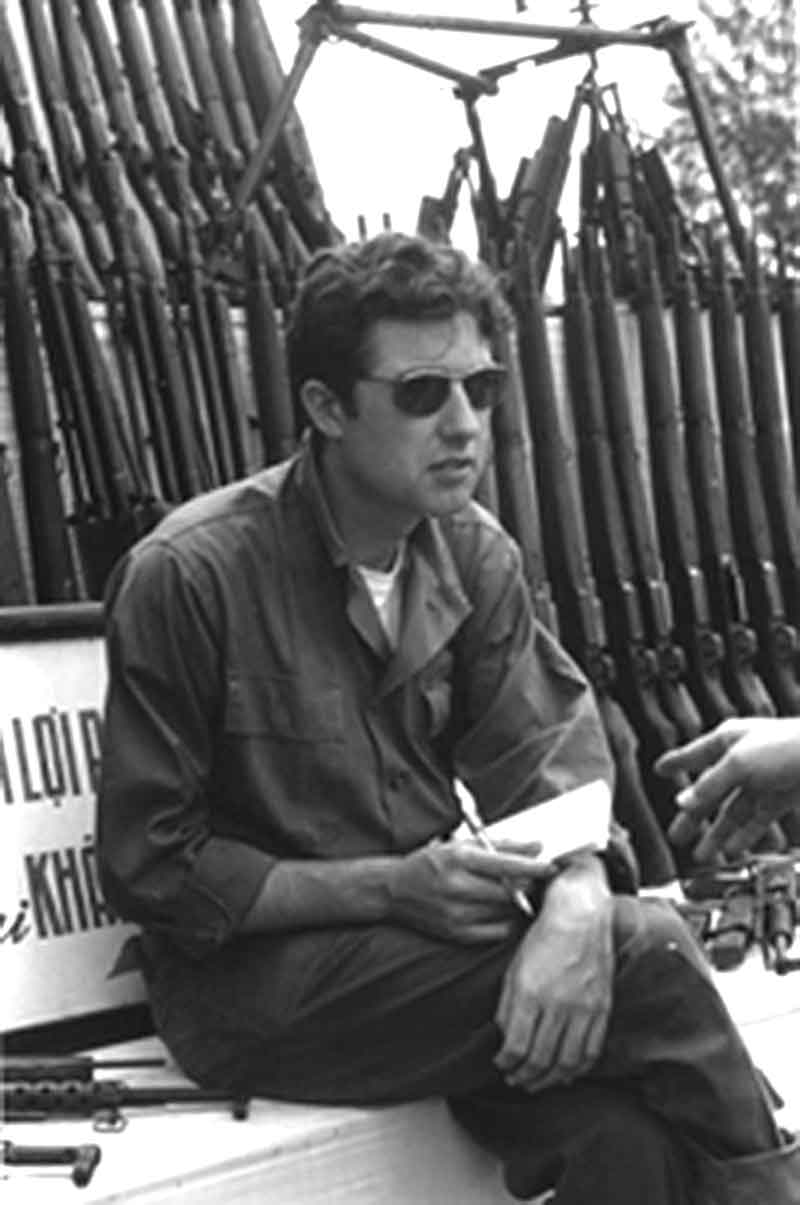

Born in New Zealand, Peter Arnett bounced around Southeast Asia as a free-lance journalist before being hired by the Associated Press in Saigon in 1962 as the U.S. was escalating its involvement in the war. He reported from Vietnam for the Associated Press for 13 years until 1975, covering some of the most intense fighting without suffering anything, he proudly recounted, worse than a scratch. He found Vietnam to be, “a witch’s brew of excitement and drama that is irresistible to journalists.” Arnett was awarded the 1966 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his extraordinary work in Vietnam. He was one of a handful of Western correspondents who remained in Saigon after it fell to North Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975. Subsequently, Arnett worked as a correspondent for CNN for 18 years. He was the first western journalist to interview Osama bin Laden. Arnett is the author of a memoir, Live from the Battlefield: From Vietnam to Baghdad, 35 Years in the World’s War Zones. In March 1997, the Journalism School at the Southern Institute of Technology in Invecargill, New Zealand, was named after him. He lives outside of Los Angeles with his wife, Nina.